Remember Social Impact Bonds? They've been around for at least a decade or so (here's an explainer I wrote in 2015). Also called "pay for success" programs, these are another instrument for privatizing public stuff.

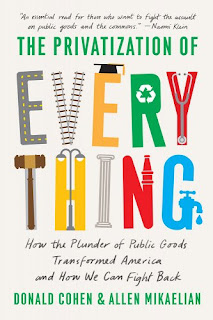

As such, they make an appearance in the new book The Privatization of Everything, a must-read from Donald Cohen and Allen Mikaelian. The book is a deep dive into the many, many, many ways in which privatization has wormed its way into the public sphere in everything from prisons to pharmaceuticals to patents to health care to municipal water systems to parking spaces. And roads. And the weather. And, of course, education. You should buy this book, and read it slowly and carefully while sitting down.

Tucked in the book (page 175) is a look at social impact bonds, and reminder of what a lousy scam these things are, a great method for "taking money from a public good and transforming it into private wealth."

What the hell are social impact bonds? This is always hard to explain, starting with the fact that they aren't actually bonds. They're a deal for private investors to fund social welfare programs and make a profit doing it, as if it were a literal investment.

The steps as listed by the Corporate Finance Institute are:

1) Identify the problem and possible solutions

2) Raise money from investors

3) Implement project

4) Assess the project's success and pay the project manager and investors

It's a chance, as one site says, for "doing good while doing well." It's also a creepy way to monetize people's struggles.

So, for instance, Cohan and Mikaelian explain one SIB program that involved veterans. The VA looked to set up a program to help deal with PTSD and veteran suicides. They ran a pilot, and the turned to investors to scale it up. Those investors would get back all their money, plus up to 18% bonus based on reaching certain numbers of veterans having sustained employment.

The price tag for the scaled program was $5 million, and the SIB "investment" certainly looks a lot like a plain old loan with a huge interest rate.

As Cohen and Mikaelian point out, there is some weird reasoning going on here. The premise for many SIB programs is that government needs private investors because government can't afford to finance the program itself--except that it's going to pay that same amount plus extra to pay the investors. It's like saying, "I can't afford to pay a babysitter $25 to babysit tonight, so will you please pay them for me, and then if they do a god job, I'll pay you $30."

Worse yet, an SIB leaves all the risk with the government. If the program doesn't succeed, it's true that they investors don't get paid--but the social need still has to be met, plus cleaning up whatever mess the failed program left.

SIBs also rest on the notion that the private sector will drive efficiency and innovation that will make the program leaner and better. This is baloney.

First, in practice, SIB pretty much never fuel innovation, because investors like sure bets. From a NYT piece about SIB's in 2015:

“The tool of ‘pay for success’ is much better suited to expanding an existing program,” Andrea Phillips, vice president of Goldman’s urban investment group, said in an interview on Wednesday. “That is something we’ve already learned through this.”

No comments:

Post a Comment