We have heard about the Honesty Gap before, way back in the spring of 2015. Achieve.org was one of the first to make some noise about it (Achieve, you may recall, was instrumental in launching Common Core), but in short order everyone was going on about it, from Jeb Bush's FEE to the Center for American Progress, Educators for Excellence, Students First--all the reformster biggies. The Honesty Gap even got its own website, which is still running today (it's owned by the Collaborative for Student Success, a CCSS promotion group that is tied directly to The Hunt Institute, which is in turn "an affiliate center" of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and lists the usual suspects as collaborators-- Gates Foundation, Achieve, NEA, The Broad Foundation, et al.)

|

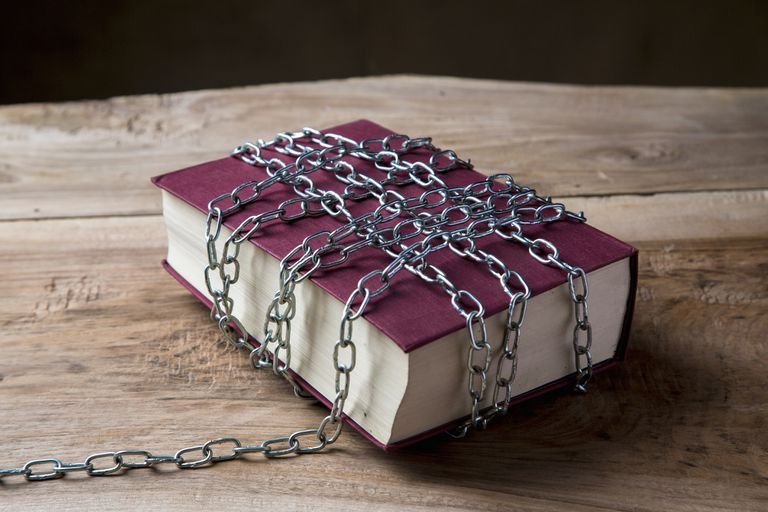

| That's one dishonest looking thermometer |

So what is The Honesty Gap? It's pretty simple--it's the observation that in many states, the proficiency rate on the NAEP doesn't match the proficiency rate on the state's Big Standardized Test. It dovetailed nicely with a theory espoused by everyone from Arne Duncan to Betsy DeVos, which was that public schools were lying about how well their students were doing, presumably to hide their own wretched failiness.

In 2015, when the Honesty Gap was having a moment, Rianna Saslow was a high school freshman at The Galloway School, a private school in Atlanta, founded in 1969. (Current tuition for grades 9-12 is $31,150.) Saslow went on to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and graduated with a BA in Political Science and a second one in Educational Equity just about six months ago. Then she went to work as a policy analyst at Education Reform Now, the 501(c)(3) arm of Democrats [sic] For Education Reform, a reformy outfit started by hedge funder Whitney Tilson to get Democrats on board with the reformster biz. To get a sense of how ERN plays, they just hosted their 12th annual Take 'Em To School Poker Tournament, where you could grab a single seat for $2,500 or a whole table for $100,000 (cocktail ticket for $250).

It's Ms. Saslow who is going to reintroduce us to the Honesty Gap, and I bring her story up for a couple of reasons.

1) A reminder that for some people, these reformy ideas really did first appear a lifetime ago. I may remember a time when the dismantling of public education was not a major narrative; folks like Ms. Saslow do not.

2) A reminder that none of this stuff dies, no matter how much it deserves to. It just keeps coming back. Therefor so must the refutations.

Saslow's piece appears at The 74, which is always a mixed bag. Some of their education journalism is top notch; their opinion section is reliably tilted in the direction of the education disruptors, defunders, and dismantlers. The piece provides a bit of an echo of The 74's earlier coverage of the Virginia report that brought up the Honesty Gap for the usual purpose--to discredit public schools.

Like too many models of the 3D crowd, this is not an honest attempt to understand a problem in education in order to find a solution. But let's take a look at Saslow's piece and see what issues are hidden there.

Saslow starts by holding up the NAEP as a "highly respected and objective set of assessments that consistently holds students to a high level of rigor and acts as a neutral referee in comparing students to one another." Wellllll.....folks have taken issue with the NAEP for as long as it has existed. One NCES study found that about half of the students rated Basic actually went on to complete a Bachelor's Degree or higher; in other words, despite what the test said, they were college ready.

Saslow suggests that it's a shortcoming that NAEP offers no individual school ratings, but that's not what it's designed for. This is a recurring problem with Big Standardized Tests, this notion that if a yardstick is good for measuring the length of a shoe, it can also measure the length of an interstate highway, or the relative humidity, or atomic weight, or how ugly that pig is. Instruments are only good at measuring what they're designed to measure.

Saslow moves on to the complaint that is the heart of the Honesty Gap. States give their own BS Tests:

But, by and large, states set a bar for academic proficiency that is lower than that for the NAEP.

Yes, states and the NAEP folks define "proficiency" differently. This has been an endless source of honest and deliberate confusion, as

folks keep making up their own definition of NAEP proficiency, rather than using the NAEP's own explanation.

Proficient does not mean "on grade level," or even "sort of above average," but

instead is roughly equivalent to a classroom A. States do not necessarily define proficiency in the same way. This is not a complicated issue. If I define "tall" as "over six feet" and you define it as "over 5 and a half feet," we will get different numbers when we analyze a group for the number of tall people. It's kind of a silly problem to have; even sillier since the NAEP folks could have solved it long ago by giving up their singular definitions of the terms involved.

Saslow rolls out some examples of how state levels of proficiency are usually higher than NAEP levels, and then she is going to drag classroom teachers into this as well by noting that classroom grades run higher, which she supports with data from ACT, a company whose whole sales pitch rests on the notion that only the scores from their product can be trusted to give a true assessment of student skills and knowledge. This is like depending on the auto industry to give you figures on the health benefits of riding a bicycle, but she's not going to mention that built in conflict.

There's a really fundamental problem--okay, two--in the whole Honesty Gap model.

Let's say I want to know what the temperature is in my living room. I use three different devices to get the temperature. If they give me different answers, the most obvious explanation is that one or more of those instruments is faulty. Learning is even more subjective and difficult to measure than temperature--when all these measures fail to match perfectly, the most obvious and likely explanation is that the measures are themselves defective.

And I certainly wouldn't accuse my mismatching temperature devices of being liars. By labeling the mismatch between instruments as an "honesty gap," we introduce the idea that the mismatch is being deliberately created by folks who are lying. The implications is that somewhere in all this there are some naughty liars (and they probably work for the public school system).

Those two factors lead me to suspect that people who talk about an Honesty Gap are not making a serious effort to solve any problems.

There are other bumps in Saslow's road. She repeats that same mistake of equating "proficient" with "on grade level." It isn't, but she uses that mistaken use in a mistaken survey to raise the old picture of families that have been misled about their children's knowledge (in 3D land, parents know their children best except when they don't have any idea what their children really know).

If families are provided with overly optimistic data, how can leaders expect their support when looking to implement robust policies and practices to improve public education?

By suggesting policies that might actually help. For instance, we could stop the practice of using low tests scores to target public schools for charterization or closure instead of actual increased support.

Closing the honesty gap requires commitment at all levels of leadership. State policymakers must ensure that their assessments are academically rigorous, and they must set benchmarks that reflect true grade-level proficiency.

Except that, in terms of NAEP scores, "grade-level proficiency" is a self-contradictory term, because "proficiency" means "well above grade level." I know, I know. I'm repeating myself. I'll stop when they do.

On the district level, administrators must ensure that instructors have access to standards-aligned, high-quality instructional materials. And within the classroom, teachers must provide consistent and reliable grades that allow students, families and school leaders to monitor progress before higher-stakes exams take place.

In other words, organize the entire school around the Big Standardized Test. Schools have already done too much of that. It is backwards and upside down and not the way to do education well (and, I'll bet, not how they do things at the Galloway School, where they don't take the Georgia state assessment).

Saslow also points out that the private sector offers some "helpful tools for accurately gauging student achievement and post-pandemic unfinished learning." I have my doubts about the "accurately" part, just as I have doubts about the process of having a problem assessed by people who want to sell you solutions to the problem.

The Honesty Gap remains a tool for marketing and pushing the old narrative that public schools are in Big Trouble, but it is itself a dishonest and sloppy argument that provides little real assistance in dealing with the actual challenges facing public education these days.