You may recall that last spring, some school district officials in Florida lost their damn minds.

Florida's test fetish became so advanced, so completely divorced from any understanding of the actual mission of schools and education and, hell, behaving like a grown human adult with responsibility for looking after children, that some district leaders interpreted state law to mean that a student who had opted out of the Big Standardized test could not be passed on to the next grade-- even if that student had a straight A report card.

Yes, I'm going to explain that again because it's so completely senseless that you might think it's just another bad typo on this blog.

Meet Chris. Chris was a third grader last year. According to Chris's report card, Chris earned passing grades in every single class. But Chris's parents said that Chris would not be taking the state test. Now Chris must repeat third grade.

Last spring some Florida education leaders took some heat over this, which is only fair because this is a decision that can only be taken as evidence that the adults in question should never be given responsibility over children ever, ever again. Gah! Look, in the world of education there are many debatable issues, many points on which I can see the other side's point of view even as I disagree vehemently with it. But what possible justification can there be for this? What possible purpose is served by forcing an otherwise successful eight year old to repeat a grade simply because that child's parents refused to comply with the state's demand to take a test? Florida has gone to the trouble of creating rules about what constitutes "participation" which it then can't explain. It is almost-- almost-- as if state education officials are mostly and only concerned that the test manufacturers have an uninterrupted revenue stream. They certainly don't give a tinker's damn about education.

On top of all that, Florida has rules in place for alternative assessments, but some edublockheads decided that those rules only apply if you have actually failed the BS Test.

So then the state and superintendents tried throwing each other under whatever buslike structures they could find. And everybody had a full summer to sort out the highly challenging puzzle of what to do with third grade students who had passed every damn class on their report cards. Because, damn, that is a puzzler there.

Too big a puzzler, apparently, because the new school year has arrived, and a whole bunch of third graders are still expected to return to third grade so they can sit through all the lessons that they already successfully completed last year. If they keep refusing to take the test, will their districts just keep them in third grade until they are twenty-one?

We may not have to find out, because now the whole slab of baloney is in court.

Fourteen parents have taken the state, Ed honcho Pam Stewart, and several local districts to court, claiming that their rights were violated.

“The negative behaviors associated with retention are exacerbated here because each of the plaintiffs’ children received a report card with passing grades, some earning straight A’s and Honor Roll for their hard work throughout the school year, but yet they will be retained in the third grade despite having no reading deficiency,” the suit says.

The suit names seven county districts ( Orange, Hernando, Osceola, Sarasota, Broward, Seminole and Pasco counties) but hopes to overturn the entire retention rule, which is so "confusing" that only some districts retained opt out children. And calling it confusing is unkind-- what seems more apparent is that, having stuck themselves with a stupid, unjust rule, the state education department doesn't have the cojones to either enforce it or scuttle it, leaving local superintendents to try to read the state tea leaves through the fog of their own intentions. You can almost hear the panicked conversation in Pam Stewart's office-- "Oh, shit!! Did we say we'd fail every single eight year old who wouldn't take the test! Well, I'm not going on television to demand eight-year-olds be forced to repeat a grade they actually passed, but I'm not going to say somneone screwed up by making such a stupid law in the first place. Just dance around it and let the superintendents take the heat."

And take heat they all will. The full text of the lawsuit is here, along with a link for anyone who wants to contribute. Because that's where we are now, folks-- parent groups have to take up a collection to go to court so that third graders who passed all their classes can be promoted to fourth grade.

Thursday, August 11, 2016

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

MA: The Swift Boating of Public Schools

Massachusetts is heating up. Perhaps no state has better exemplified the fierce debate between public school advocates and fans of modern education reform. Ed reformers captured the governor's seat, the mayoral position of Boston, commissioner of education, and the secretary of education offices, and yet have consistently run into trouble since the day they convinced the commonwealth to abandon its previous education standards in favor of the Common Core Standards-- which were rated inferior to the Massachusetts standards even by the guys paid to promote the Core.

These days the debate has shifted to the issue of charter schools. Specifically, the charter cap. Currently Massachusetts has a limit on how many charter schools can operate in the Pilgrim state. The people who make a living in the charter biz would like to see that cap lifted, and the whole business will be put to a public referendum in November.

So well-heeled charter fans have collected a few million dollars, and they have hired DC-based SRCP Media, most famous for the Swift Boat campaign that sank John Kerry's candidacy. The Swift Boat campaign was also a demonstration of the fine old political rule, "When the truth is not on your side, construct a new truth."

So is SRCP manufacturing truth in Massachusetts?

Spoiler alert: Yes.

It appears that the multi-million dollar ad buy will lean on that old favorite-- charter schools are public schools. And when I say "favorite," what I actually mean is "lie." But let's look at the whole thirty seconds.

We open with a Mrs. Ingall, who is listed as a "public school teacher." That would be Dana Ingall, a teacher at the Match Charter School, whose bio says that she attended University of Michigan, joined Teach for America in 2011, was sent to Delaware and Harlem, and earned an Elementary Ed Degree from Wilmington University. She hasn't been in Boston long.

But she still knows how to say "Massachusetts public charter schools are among the best in the country," which is sort of true, if all you care about are test scores, and you're cool with charters that keep their test scores high by suspending huge numbers of students, carefully avoiding any challenging students (like the non-English speaking ones), and chasing out those who don't get great scores.

"Our charter schools are public," says Ingall. And she seems like a nice person, so I will assume that someone at SRCP handed her a script and told her to repeat that lie. We'll come back to it in a bit. She goes on to note that charters have longer school days and a "proven record" of helping students in underperforming areas "succeed" which, again, doesn't mean anything except "get a good test score." I also like the careful distinction of helping students in underperforming areas, which is less impressive than helping students from underperforming areas or, since we're claiming to be a public school, helping ALL students from that area.

Then Voice Over Man comes on to tell us that Question 2 will expand charter school access and "result in more funding for public school" which probably refers to the state funding formula. When Chris goes to a charter, the per-pupil money follows Chris, but an amount is paid to Chris's public school, to soften the financial blow. Massachusetts' formula is probably the best in the nation-- but that "increase in education spending" would be on the order of a billion dollar. Which means one of a couple of things would happen-- either the taxpayers would be asked to cover that billion-dollar payout by raising taxes, or the state would find the billion in charter cost coverage by cutting some other part of education spending. So, for instance, Pat doesn't get to go to pre-school because the state has to pay to send Chris to a charter. Any way you cut it, the cost of sending Chris to a private school will be felt by taxpayers and public education.

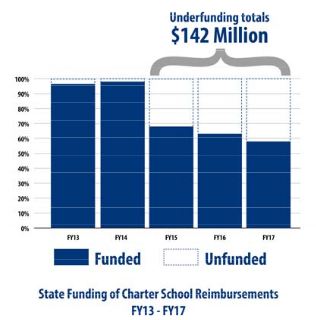

Oh, and Chapter 46, the law under which all that reimbursing happens-- it hasnever not been fully funded in the past several years*, so local districts have to make up the difference. When Chris goes to charter school, the local taxpayers have to kick in to pay for it. [Update: Courtesy of Save Our Public Schools MA, here's a more detailed look at just how underfunded charter reimbursement of public schools is-- and will be]

Ingall returns to say "Every parent should be able to choose the school that's best for their child," but all the charter expansion in the world will not result in that scenario. It is already clear that Massachusetts' system of charterizing allows charters to choose which students they would like. Parents are no more able to choose any school they'd like their child to attend than high school graduates are able to choose any college they'd like to attend.

Finally, the tag line-- Vote yes on 2 for stronger public schools.

The ad is bankrolled by Great Schools Massachusetts, a group that exists just to get the charter cap lifted. They are an umbrella that covers long-time reformster groups like Families for Excellent Schools, an astroturf group that fronts for Wall Street investors.

Other Swifties

Peruse the Great Schools Massachusetts site and see other examples of Totally Not Grass Roots in action. Here's the professionally filmed and staged launch of the site, featuring an appearance by Governor Baker, who talks about students stuck in bad schools in bad neighborhoods as if he had no idea, no power, no say in getting state resources to those schools in order to improve them. But no-- the only hope is to open a charter schools so that a favored few of those students can be rescued in a lifeboat made with planks from the hull of the ship that's carrying everyone else.

Or listen to Dawn tell the story of how her son was rejected by a dozen charter schools until KIPP finally accepted him. The solution to this, somehow, is more charters and not a better investment in public schools.

The Big Charter Lie

The big lie in all of this push is the suggestion, hint, or sometimes outright statement that charters are public schools.

Public schools must take-- and keep-- all students-- at any time. Charters do not. Look at the attrition rates. Look at the limited population of special needs students. Look at the suspension rates (a good way to communicate that a student is not welcome). Look at the dismal charter graduation rate for young black men.

Public schools must operate with transparency and accountability. All board meetings must be public. All financial records must be readily available to any taxpayer who asks to see them. Charters have repeatedly gone to court to assert that, like any private business, they do not have to share financial information with anyone.

Public schools must follow certain laws in dealing with employees and students. Charters do not and, again, have gone to court repeatedly to assert that they are not subject to the same rules as public schools. And while they love being able to work without a union or a contract, they are also happy to avoid following any protections for student rights. In fact, these two "freedoms" can result in teachers being fired for standing up for student rights.

Public schools must stay open and operating as long as the public demands it. Charters can close at any time they wish, and because they are businesses, they will close at times that make business sense, not times that make educational sense, or that most weigh the needs of the students.

Courts have repeatedly found that charter schools are not "public actors"

Charter investors have made it plain that they believe they are investing in a private business, not a public school, "time and time and time and time and time again." And they do it in part by turning public assets (like school buildings) into private assets.

And the thing is, virtually everybody knows this. Public school supporters, charter advocates-- virtually everyone knows that charters and public schools are not the same thing.

In fact, in the last year we've seen a rise in charter fans pushing a "Can't we all get along?" narrative. The director of Philadelphia Charters for Excellence last fall said "It is time to move past the adversarial position of 'traditional vs. charter' schools and work to create an environment where both sectors can flourish." In March, Massachusett's SouthCoast Today joined some charter chiefs in asking, "Can charter and district schools be partners in education?"

It's a change from the older trope that free market competition would drive everyone to excellence. But the two approaches have one thing in common-- they recognize that charter schools are not public schools.

Nor are they treated the same by Massachusetts, which makes sure that the charter gets every cent coming to it, but looks at the public school system and shrugs, "Talk to your local taxpayers."

Nor will things be sorted out by the free market. Charter operators already know this-- several brick and mortar charter folks have spoken up to say that the government needs to clamp down on all the crappy cyber-charters. But by their own theory, such intervention shouldn't be needed because parents will vote for quality with their feet-- but the free market doesn't work for charter schools at all, even when it is tilted to treat them one way and public schools another.

So when a long-time charter booster like Peter Cunningham, former spokesmouth for Arne Duncan's Department of Education and current word-ronin for well-heeled reform investors, writes something like "First of all, charter schools are public schools. Arguing that charters take money from traditional schools is like arguing that a younger sibling takes parental attention away from an older sibling." He knows he's shoveling baloney. It was far more honest when he tweeted

Not add to or support or enhance. Supplant. Replace.

Replace a school system with democratically-elected leadership, a system that must teach all students, a system in which taxpayers have a say, a system that comes with a long-term commitment-- replace that with a system that entitles some students to attend any private school that they can convince to accept them. And keep them. And stay open.

Are public schools perfect as is? Not even close. But the solution is not to rescue a favored few at the cost of making things worse for the many left behind. If charter advocates wanted to approach this honestly, here's what their proposal would say--

Vote to have your taxes raised to finance a new entitlement for every child to have the option of attending private school at taxpayer expense. Vote to shut down public schools and replace them with schools that aren't any better, won't serve some of your children, and aren't accountable to you, ever.

Let the swift boaters make an ad to sell that.

*Corrected from original version once I found the actual information.

These days the debate has shifted to the issue of charter schools. Specifically, the charter cap. Currently Massachusetts has a limit on how many charter schools can operate in the Pilgrim state. The people who make a living in the charter biz would like to see that cap lifted, and the whole business will be put to a public referendum in November.

So well-heeled charter fans have collected a few million dollars, and they have hired DC-based SRCP Media, most famous for the Swift Boat campaign that sank John Kerry's candidacy. The Swift Boat campaign was also a demonstration of the fine old political rule, "When the truth is not on your side, construct a new truth."

So is SRCP manufacturing truth in Massachusetts?

Spoiler alert: Yes.

It appears that the multi-million dollar ad buy will lean on that old favorite-- charter schools are public schools. And when I say "favorite," what I actually mean is "lie." But let's look at the whole thirty seconds.

We open with a Mrs. Ingall, who is listed as a "public school teacher." That would be Dana Ingall, a teacher at the Match Charter School, whose bio says that she attended University of Michigan, joined Teach for America in 2011, was sent to Delaware and Harlem, and earned an Elementary Ed Degree from Wilmington University. She hasn't been in Boston long.

But she still knows how to say "Massachusetts public charter schools are among the best in the country," which is sort of true, if all you care about are test scores, and you're cool with charters that keep their test scores high by suspending huge numbers of students, carefully avoiding any challenging students (like the non-English speaking ones), and chasing out those who don't get great scores.

"Our charter schools are public," says Ingall. And she seems like a nice person, so I will assume that someone at SRCP handed her a script and told her to repeat that lie. We'll come back to it in a bit. She goes on to note that charters have longer school days and a "proven record" of helping students in underperforming areas "succeed" which, again, doesn't mean anything except "get a good test score." I also like the careful distinction of helping students in underperforming areas, which is less impressive than helping students from underperforming areas or, since we're claiming to be a public school, helping ALL students from that area.

Then Voice Over Man comes on to tell us that Question 2 will expand charter school access and "result in more funding for public school" which probably refers to the state funding formula. When Chris goes to a charter, the per-pupil money follows Chris, but an amount is paid to Chris's public school, to soften the financial blow. Massachusetts' formula is probably the best in the nation-- but that "increase in education spending" would be on the order of a billion dollar. Which means one of a couple of things would happen-- either the taxpayers would be asked to cover that billion-dollar payout by raising taxes, or the state would find the billion in charter cost coverage by cutting some other part of education spending. So, for instance, Pat doesn't get to go to pre-school because the state has to pay to send Chris to a charter. Any way you cut it, the cost of sending Chris to a private school will be felt by taxpayers and public education.

Oh, and Chapter 46, the law under which all that reimbursing happens-- it has

Ingall returns to say "Every parent should be able to choose the school that's best for their child," but all the charter expansion in the world will not result in that scenario. It is already clear that Massachusetts' system of charterizing allows charters to choose which students they would like. Parents are no more able to choose any school they'd like their child to attend than high school graduates are able to choose any college they'd like to attend.

Finally, the tag line-- Vote yes on 2 for stronger public schools.

The ad is bankrolled by Great Schools Massachusetts, a group that exists just to get the charter cap lifted. They are an umbrella that covers long-time reformster groups like Families for Excellent Schools, an astroturf group that fronts for Wall Street investors.

Other Swifties

Peruse the Great Schools Massachusetts site and see other examples of Totally Not Grass Roots in action. Here's the professionally filmed and staged launch of the site, featuring an appearance by Governor Baker, who talks about students stuck in bad schools in bad neighborhoods as if he had no idea, no power, no say in getting state resources to those schools in order to improve them. But no-- the only hope is to open a charter schools so that a favored few of those students can be rescued in a lifeboat made with planks from the hull of the ship that's carrying everyone else.

Or listen to Dawn tell the story of how her son was rejected by a dozen charter schools until KIPP finally accepted him. The solution to this, somehow, is more charters and not a better investment in public schools.

The Big Charter Lie

The big lie in all of this push is the suggestion, hint, or sometimes outright statement that charters are public schools.

Public schools must take-- and keep-- all students-- at any time. Charters do not. Look at the attrition rates. Look at the limited population of special needs students. Look at the suspension rates (a good way to communicate that a student is not welcome). Look at the dismal charter graduation rate for young black men.

Public schools must operate with transparency and accountability. All board meetings must be public. All financial records must be readily available to any taxpayer who asks to see them. Charters have repeatedly gone to court to assert that, like any private business, they do not have to share financial information with anyone.

Public schools must follow certain laws in dealing with employees and students. Charters do not and, again, have gone to court repeatedly to assert that they are not subject to the same rules as public schools. And while they love being able to work without a union or a contract, they are also happy to avoid following any protections for student rights. In fact, these two "freedoms" can result in teachers being fired for standing up for student rights.

Public schools must stay open and operating as long as the public demands it. Charters can close at any time they wish, and because they are businesses, they will close at times that make business sense, not times that make educational sense, or that most weigh the needs of the students.

Courts have repeatedly found that charter schools are not "public actors"

Charter investors have made it plain that they believe they are investing in a private business, not a public school, "time and time and time and time and time again." And they do it in part by turning public assets (like school buildings) into private assets.

And the thing is, virtually everybody knows this. Public school supporters, charter advocates-- virtually everyone knows that charters and public schools are not the same thing.

In fact, in the last year we've seen a rise in charter fans pushing a "Can't we all get along?" narrative. The director of Philadelphia Charters for Excellence last fall said "It is time to move past the adversarial position of 'traditional vs. charter' schools and work to create an environment where both sectors can flourish." In March, Massachusett's SouthCoast Today joined some charter chiefs in asking, "Can charter and district schools be partners in education?"

It's a change from the older trope that free market competition would drive everyone to excellence. But the two approaches have one thing in common-- they recognize that charter schools are not public schools.

Nor are they treated the same by Massachusetts, which makes sure that the charter gets every cent coming to it, but looks at the public school system and shrugs, "Talk to your local taxpayers."

Nor will things be sorted out by the free market. Charter operators already know this-- several brick and mortar charter folks have spoken up to say that the government needs to clamp down on all the crappy cyber-charters. But by their own theory, such intervention shouldn't be needed because parents will vote for quality with their feet-- but the free market doesn't work for charter schools at all, even when it is tilted to treat them one way and public schools another.

So when a long-time charter booster like Peter Cunningham, former spokesmouth for Arne Duncan's Department of Education and current word-ronin for well-heeled reform investors, writes something like "First of all, charter schools are public schools. Arguing that charters take money from traditional schools is like arguing that a younger sibling takes parental attention away from an older sibling." He knows he's shoveling baloney. It was far more honest when he tweeted

By definition charters supplant public schools. We don't have infinite number of kids. Can't protect schools parents don't want. @kombiz— Peter Cunningham (@PCunningham57) August 9, 2016

Not add to or support or enhance. Supplant. Replace.

Replace a school system with democratically-elected leadership, a system that must teach all students, a system in which taxpayers have a say, a system that comes with a long-term commitment-- replace that with a system that entitles some students to attend any private school that they can convince to accept them. And keep them. And stay open.

Are public schools perfect as is? Not even close. But the solution is not to rescue a favored few at the cost of making things worse for the many left behind. If charter advocates wanted to approach this honestly, here's what their proposal would say--

Vote to have your taxes raised to finance a new entitlement for every child to have the option of attending private school at taxpayer expense. Vote to shut down public schools and replace them with schools that aren't any better, won't serve some of your children, and aren't accountable to you, ever.

Let the swift boaters make an ad to sell that.

*Corrected from original version once I found the actual information.

ACLU: Illegal California Charter Practices

The ACLU recently issued a report outlining a variety of widespread illegal practices among California charter schools. The report is worth reading in detail because it gives an impression of just how widespread these practices of restricting student enrollment are, creating one more situation in which "school choice" means that schools get to choose students.

California law is pretty clear that charters may not "enact admissions requirements or other barriers to enrollment and must admit all students who apply, just as traditional public schools cannot turn away students." How do California charters violate those rules? Let's count the ways.

Deny admission to academically struggling students.

Charters are not allowed to bar students because of academic requirements, but at least twenty-two do, with everything from requiring particular coursework to a cut-off grade at their previous public school.

Deny extra chances to struggling students.

Charters should give struggling students more chances to succeed, but some penalize students for failing to keep up academically.

Barriers to English Language Learners.

While some charters work hard to assist ELL students, others have policies in place to make it harder for such students, some as transparent as requiring a minimum score on a language arts assessment (one school requires the applicant to be no more than one year behind grade level). Others use more subtle techniques, like including no Spanish on applications and school materials. But charters may not legally bar ELL students, and they must provide appropriate programs. No, you can't just say, "We do all our instruction in English, chico. You'll just have to stay with us. Catch up or get out."

Use interviews and essays.

Charters may not use interviews or admissions essays to determine what students they will accept. Some do it anyway. Some work around the law by having interviews and essays but claiming not to use them. A) Nobody actually believes that. B) The very presence of such a process intimidates some students with less academically-swell backgrounds. Example:

In a 2 to 3 paragraph essay (minimum 5 sentences per paragraph), tell us why you want to come to OCEAA – what interests you most about the school? You must use proper grammar and punctuation.

Requiring SSN and birth certificate.

Not allowed to do that. Some do anyway. One more hurdle that discourages the Wrong Sort of Student from even applying.

Requiring donations of time from parents.

Some charters require parents to donate time and sweat equity to the school. It's a handy way to avoid costs like janitorial and other simple positions. That's illegal, and of course, a problem for working parents. Some schools helpfully allow that parents who don't have the time can contribute money instead. Again, even the appearance of such policies is enough to scare some parents away.

Pushing out students with low grades.

Flat out illegal. Charters cannot, for instance, expel students for having a low GPA, or even threaten to. Yet many do.

The report includes many, many examples, most of which fall into the "I know this is only a single anecdote, but if this happens even once that's one time too many, and why didn't someone get in big trouble over it?!"

California has written charter school law that says just what charter law should say-- that a charter school must accept every student that shows up at its door, and can deny them only for no reason other than being out of space. That's what the law should say. But having the law say that is not enough if charters can get away with choosing not to follow it. Will shining light on these illegal practices end them? We can only hope.

California law is pretty clear that charters may not "enact admissions requirements or other barriers to enrollment and must admit all students who apply, just as traditional public schools cannot turn away students." How do California charters violate those rules? Let's count the ways.

Deny admission to academically struggling students.

Charters are not allowed to bar students because of academic requirements, but at least twenty-two do, with everything from requiring particular coursework to a cut-off grade at their previous public school.

Deny extra chances to struggling students.

Charters should give struggling students more chances to succeed, but some penalize students for failing to keep up academically.

Barriers to English Language Learners.

While some charters work hard to assist ELL students, others have policies in place to make it harder for such students, some as transparent as requiring a minimum score on a language arts assessment (one school requires the applicant to be no more than one year behind grade level). Others use more subtle techniques, like including no Spanish on applications and school materials. But charters may not legally bar ELL students, and they must provide appropriate programs. No, you can't just say, "We do all our instruction in English, chico. You'll just have to stay with us. Catch up or get out."

Use interviews and essays.

Charters may not use interviews or admissions essays to determine what students they will accept. Some do it anyway. Some work around the law by having interviews and essays but claiming not to use them. A) Nobody actually believes that. B) The very presence of such a process intimidates some students with less academically-swell backgrounds. Example:

In a 2 to 3 paragraph essay (minimum 5 sentences per paragraph), tell us why you want to come to OCEAA – what interests you most about the school? You must use proper grammar and punctuation.

Requiring SSN and birth certificate.

Not allowed to do that. Some do anyway. One more hurdle that discourages the Wrong Sort of Student from even applying.

Requiring donations of time from parents.

Some charters require parents to donate time and sweat equity to the school. It's a handy way to avoid costs like janitorial and other simple positions. That's illegal, and of course, a problem for working parents. Some schools helpfully allow that parents who don't have the time can contribute money instead. Again, even the appearance of such policies is enough to scare some parents away.

Pushing out students with low grades.

Flat out illegal. Charters cannot, for instance, expel students for having a low GPA, or even threaten to. Yet many do.

The report includes many, many examples, most of which fall into the "I know this is only a single anecdote, but if this happens even once that's one time too many, and why didn't someone get in big trouble over it?!"

California has written charter school law that says just what charter law should say-- that a charter school must accept every student that shows up at its door, and can deny them only for no reason other than being out of space. That's what the law should say. But having the law say that is not enough if charters can get away with choosing not to follow it. Will shining light on these illegal practices end them? We can only hope.

Refresh the Resolve

Of course, we're all on different schedules across the country, but here in NW PA, it's a little under three weeks till school gets started. (Boy, shouldn't we do something about that? I mean, a student moving from PA to TN would find themselves suddenly several days behind, or one moving the other way would have to do the first day all over again, so we probably need a Common Core School Calendar so that we are all always on the same page on the same day. But I digress.)

In the weeks before school starts, I try to focus on my personal big picture to get myself cranked back up for school.

You know how it is. In the back of your head, you have ideas about big important concepts and respecting and building on the humanity of every student and over-arching themes that you want to thread through the whole year's instruction. And then before you know it, it's October and your thoughts about the many important domains of student learning and growth are being pushed aside by concerns like if Chris laughs that annoying laugh at some inappropriate moment one more time, you are going to bust a gut.

There is a dailiness to teaching that can get in the way of our highest, best intentions. I want to stay focused on global objectives about language use, but right now I have to make sure I have enough scissors that work safely. I want to make sure each class starts with a warm welcome, but I just found out that the copy room didn't send down all my copies. I want to have a full and open discussion of the readings, but today the period was cut short and interrupted three times.

So it's an important part of my work to try to keep my focus, remember what I'm doing and why. It has become even more important for me since I've spent so much time staring into the maw of education reform and the many forces intent on breaking down public education in this country (and others).

When you first learn to drive, you have to learn where to look. If you get so scared of the telephone pole that you stare at it, you will then drive straight toward it. You can't ignore the obstacles, and you have to pay attention so you can react if some hazard throws itself in your path, but first and foremost you have to keep your eyes on the road, keep your gaze focused on the place you want to go.

So that is my August practice. Get out the stack of education books that I've been meaning to read. Spend some time being mindful of why I do it, and what it is I want to do. Refresh my resolve.

This year, I'm going to extend the exercise to this space with a series of essays to help me keep my focus where it needs to be. because no matter how many years I have done this, there's always more to work on, and some of the work is better done on days when I'm not trying to get copies made.

In the weeks before school starts, I try to focus on my personal big picture to get myself cranked back up for school.

You know how it is. In the back of your head, you have ideas about big important concepts and respecting and building on the humanity of every student and over-arching themes that you want to thread through the whole year's instruction. And then before you know it, it's October and your thoughts about the many important domains of student learning and growth are being pushed aside by concerns like if Chris laughs that annoying laugh at some inappropriate moment one more time, you are going to bust a gut.

There is a dailiness to teaching that can get in the way of our highest, best intentions. I want to stay focused on global objectives about language use, but right now I have to make sure I have enough scissors that work safely. I want to make sure each class starts with a warm welcome, but I just found out that the copy room didn't send down all my copies. I want to have a full and open discussion of the readings, but today the period was cut short and interrupted three times.

So it's an important part of my work to try to keep my focus, remember what I'm doing and why. It has become even more important for me since I've spent so much time staring into the maw of education reform and the many forces intent on breaking down public education in this country (and others).

When you first learn to drive, you have to learn where to look. If you get so scared of the telephone pole that you stare at it, you will then drive straight toward it. You can't ignore the obstacles, and you have to pay attention so you can react if some hazard throws itself in your path, but first and foremost you have to keep your eyes on the road, keep your gaze focused on the place you want to go.

So that is my August practice. Get out the stack of education books that I've been meaning to read. Spend some time being mindful of why I do it, and what it is I want to do. Refresh my resolve.

This year, I'm going to extend the exercise to this space with a series of essays to help me keep my focus where it needs to be. because no matter how many years I have done this, there's always more to work on, and some of the work is better done on days when I'm not trying to get copies made.

The Global Agenda for Monetizing Education

In today's USNews, education historian and activist Diane Ravitch talks about the worldwide movement to buy and sell education, to privatize it, to attack "the very concept of public education."

You don't have to look hard to find some of the folks who are heavily invested in driving what some call the Global Education Reform Movement (GERM). Take for instance this white paper presented to the World Economic Forum-- "Unleashing Greatness: Nine Plays To Spark Innovation in Education" (and briefly covered in Ravitch's blog)

The paper is almost as interesting or who's behind it as for what's in it-- but I'm going to look at what's in it first. Then we'll take a look at the GERMy minds that created this monstrosity.

The Nine Big Plays

It makes sense that the Global Agenda for Monetizing Education (GAME) would talk about the kind of "plays" needed to win. These guys narrowed the list down to nine.

The nine big plays come courtesy of Michael Barber, the chief of Pearson, and Joel Klein, previously the reformster-in-chief of education in New York City and, well, he's logged many fine achievements, such as awarding a multi-million dollar contract to News Corp for a big edu-data-crunching program called ARIS just before he left New York schools to go work for News Corp, shortly before NYC schools scrapped ARIS because it was junk. Klein also ran Amplify, Rupert Murdoch's big shot at making some big edu-bucks. Amplify lost about half a billion-with-a-B dollars before Murdoch just sold it off. Now on this paper, Klein lists his employment as Chief Policy and Strategy Officer, Oscar Insurance.

You will not find two more ardent supporters of privatization, not just of education itself, but of education as a tool for getting Big Data's hands on All the Data about All the Humans. So what are their nine great "plays"?

1. Provide a compelling vision for the future.

A compelling vision can align internal and external stakeholders around the need for change.

External stakeholders? I am stumped about what an external stakeholder in education would be, unless it's an investor from outside the community. The vision should also get everyone on board with what changes "should come," which is a trademark Barberism-- we know what your community needs, so just let us do it to you, because we are lifting up the white man's burden.

Each play has some illustrative case studies, and this point includes New Orleans, so I guess the point is that you need to have a compelling vision, whether you can actually deliver it or not.

2. Set ambitious goals that force innovation.

I'm inclined to paraphrase that as "set a goal so big that the locals will have to hire outside people to accomplish it." But also, set small specific goals and "demonstrate to educators and administrators how they can contribute to the goals." In other words, let the locals know what they can do to help out the people who have now taken over control and ownership of the local school system. In other words, let them know what their place is in the new order of things (spoiler alert: it is down in the cheap seats with the rest of the hired help).

The exemplar here is Chile, a Milton Friedman paradise where teachers are chattel and market-driven schools have solidly cemented social and economic divisions between classes.

3. Create choice and competition.

Choice and competition can create pressure for schools to perform better.

Can they? Because there's no evidence anywhere that they do, and even this write-up cautions that there are some possible pitfalls. Vouchers and choice work great for privatizers looking to make a buck in the education biz. However, choice works poorly for teachers, schools, communities, students, parents, taxpayers, and anyone else who isn't already rich.

Case studies here include New York City and the completely unfounded claim that NYC charters-- well, actually what it says is that students "served by charter schools outperform their peers" which is true in the sense that NYC charters prefer and select to serve the higher performing students. But that proves nothing about choice or competition. The other case study is, I kid you not, a Pearson investment fund that has done pretty well with choice markets. So, yes, my point-- choice is great if you're trying to make money.

4. Pick many winners.

The advice here is again aimed at investors-- when choice opens up, invest in many players so that you're sure to get a good return.

Of course, picking winners also means picking losers. The report cites Race to the Top as a good example, and it makes me realize that RTTT did break with NCLB in one important way-- while NCLB insisted that all students and schools become winners (through force of will or coercion or magic beans), RTTT set out to very deliberately label a bunch of students, teachers, schools, districts and states as losers. So, yay.

5. Benchmark and track progress.

The school leader (because our model here is schools run by visionary powerful CEOs) needs to have all that data so he can keep everyone on track. This data will also be useful for the civilians, and it should include comparable data that we can weigh against other schools, states, nations, and planets. One size fits all education is super because it's the easiest kind to create spreadsheets for.

6. Evaluate and share the performance of new innovations.

Except when we're competing as a way of improving? This is always the part I find mysterious about these free market fans-- the competition game is great unless I am winning, in which case people should compete for my favor, but I should not have to compete with anyone else. Bring me your great programs as tribute, and I will reward you by giving those techniques to the people you must compete against. Is there any corporate or political structure anywhere in all of human history that actually works that way?

7. Combine greater accountability and autonomy.

Another piece of thick-sliced baloney. We are great at giving charters autonomy, but we have been very insistent that they not be accountable to anyone. Their finances are to be kept secret, their education programs proprietary secrets, and their leadership should never actually have to answer directly to taxpayer and voters.

No, accountability here means that the service provider should be accountable to the corporate bosses who sweep up the proceeds from the business. Accountable to parents and students and taxpayers? That's crazy talk. They are going to cite a study by the Boston Foundation, a group set up expressly to help pry schools away from elected school boards so that visionary CEOs can have the freedom to do what they will and never have to answer to any of the little people.

8. Invest and empower agents of change.

Get your people in positions where they can make sure that the rules and the enforcement of the rules go your way. Spend whatever it takes to do that.

9. Reward successes (and productive failures).

The unstated but very important rest of this sentence is "and nobody else. And make sure that you are the one who defines success." Again, there's no proof that merit pay works, but it works great for the people who are doing the paying, because it's cheap. So let's keep doing it.

So who are these guys?

Barber and Klein would be enough of a team all by themselves. But they're not on their own here.

The parent group is the World Economic Forum, often referred to by its annual meeting location at Davos, Switzerland. The organization was found in 1971 and launched by inviting almost 450 corporate heads to come together and figure out how they would manage the world.

To better manage the world, the WEF has what it calls Global Agenda Councils.

The Global Agenda Councils are a network of invitation-only groups that study the most pressing issues facing the world. Each council is made up of 15-20 experts, who come together to provide interdisciplinary thinking, stimulate dialogue, shape agendas and drive initiatives. Council Members meet annually at the Summit on the Global Agenda, the world’s largest brainstorming event, which is hosted in partnership with the government of the United Arab Emirates.

So who are the invitation-only experts of the Global Agenda Council on Education? Well Barber is the chair, and Klein the vice-chair.

Omar K. Alghanim, Chief Executive Officer, Alghanim Industries A multi-billion dollar international conglomerate based in Kuwait, with their fingers in literally hundreds of pies from Delco to Avis.

Claudia Costin, Senior Director, Global Education, The World Bank

Jamil F. Dandany, Director, Education and Academic Programmes, Saudi Aramco A Saudi oil company, "where energy is opportunity."

Jose Ferreira, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Knewton Inc. The arm of Pearson devoted to big time data mining.

Jiang Guohua, Associate Dean, Peking University Graduate School

Shiv V. Khemka, Vice-Chairman, SUN Group Investment and private equity management group, specializing in emerging markets like India and Russia

Brij Kothari, Director, PlanetRead

Paul Kruchoski, Policy Adviser, US Department of State Yes, the US has a rep on this council, but not from Education-- from State

Rolf Landua, Head, Education Group, European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)

Mona Mourshed, Director, McKinsey & Company Consulting and investment experts, with a long history of pushing for privatization

Anne McElvoy Editor, Public Policy and Education, The Economist

John P. Puckett, Senior Partner and Managing Director, The Boston Consulting Group Like McKinsey, experts in explaining how to dismantle public education for fun and profit

Shiza Shahid, Co-Founder and Global Ambassador, Malala Fund

Andreas Schleicher, Head, Indicators and Analysis Division, OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)

Gracia S. Ugut, Executive Director, Lippo Education Initiatives, Lippo Education Initiatives One of Indonesia's biggest conglomerates. Fun story. The founder-CEO James Riedy was for a time barred from traveling to the US because of illegal contributions to Bill Clinton's campaign.

Dino Varkey, Group Executive Director and Board Member, GEMS Education Worldwide private school chain based in Dubai.

Rebecca Winthrop, Senior Fellow and Director, The Brookings Institution

Well, that just looks like a swell bunch of folks to unilaterally determine what education should look like on a global scale. What a fine, respectable group of wolves to oversee the proper management of sheep.

WEF is a systems bunch of folks, who look to make systems that work for them:

The global, regional and industry challenges facing the world are the result of many “systems” .... To enable our constituents to make sustained positive change, we work with them to understand and influence the entirety of the system that affects the challenges and opportunities they are trying to

address.

Yikes. When the world's governments and systems just don't work the way you want them to, there's really nothing else to do but override them with your own corporate super-government. The education GAME is just one small event in the Oligarchy Olympics.

You don't have to look hard to find some of the folks who are heavily invested in driving what some call the Global Education Reform Movement (GERM). Take for instance this white paper presented to the World Economic Forum-- "Unleashing Greatness: Nine Plays To Spark Innovation in Education" (and briefly covered in Ravitch's blog)

The paper is almost as interesting or who's behind it as for what's in it-- but I'm going to look at what's in it first. Then we'll take a look at the GERMy minds that created this monstrosity.

The Nine Big Plays

It makes sense that the Global Agenda for Monetizing Education (GAME) would talk about the kind of "plays" needed to win. These guys narrowed the list down to nine.

The nine big plays come courtesy of Michael Barber, the chief of Pearson, and Joel Klein, previously the reformster-in-chief of education in New York City and, well, he's logged many fine achievements, such as awarding a multi-million dollar contract to News Corp for a big edu-data-crunching program called ARIS just before he left New York schools to go work for News Corp, shortly before NYC schools scrapped ARIS because it was junk. Klein also ran Amplify, Rupert Murdoch's big shot at making some big edu-bucks. Amplify lost about half a billion-with-a-B dollars before Murdoch just sold it off. Now on this paper, Klein lists his employment as Chief Policy and Strategy Officer, Oscar Insurance.

You will not find two more ardent supporters of privatization, not just of education itself, but of education as a tool for getting Big Data's hands on All the Data about All the Humans. So what are their nine great "plays"?

1. Provide a compelling vision for the future.

A compelling vision can align internal and external stakeholders around the need for change.

External stakeholders? I am stumped about what an external stakeholder in education would be, unless it's an investor from outside the community. The vision should also get everyone on board with what changes "should come," which is a trademark Barberism-- we know what your community needs, so just let us do it to you, because we are lifting up the white man's burden.

Each play has some illustrative case studies, and this point includes New Orleans, so I guess the point is that you need to have a compelling vision, whether you can actually deliver it or not.

2. Set ambitious goals that force innovation.

I'm inclined to paraphrase that as "set a goal so big that the locals will have to hire outside people to accomplish it." But also, set small specific goals and "demonstrate to educators and administrators how they can contribute to the goals." In other words, let the locals know what they can do to help out the people who have now taken over control and ownership of the local school system. In other words, let them know what their place is in the new order of things (spoiler alert: it is down in the cheap seats with the rest of the hired help).

The exemplar here is Chile, a Milton Friedman paradise where teachers are chattel and market-driven schools have solidly cemented social and economic divisions between classes.

3. Create choice and competition.

Choice and competition can create pressure for schools to perform better.

Can they? Because there's no evidence anywhere that they do, and even this write-up cautions that there are some possible pitfalls. Vouchers and choice work great for privatizers looking to make a buck in the education biz. However, choice works poorly for teachers, schools, communities, students, parents, taxpayers, and anyone else who isn't already rich.

Case studies here include New York City and the completely unfounded claim that NYC charters-- well, actually what it says is that students "served by charter schools outperform their peers" which is true in the sense that NYC charters prefer and select to serve the higher performing students. But that proves nothing about choice or competition. The other case study is, I kid you not, a Pearson investment fund that has done pretty well with choice markets. So, yes, my point-- choice is great if you're trying to make money.

4. Pick many winners.

The advice here is again aimed at investors-- when choice opens up, invest in many players so that you're sure to get a good return.

Of course, picking winners also means picking losers. The report cites Race to the Top as a good example, and it makes me realize that RTTT did break with NCLB in one important way-- while NCLB insisted that all students and schools become winners (through force of will or coercion or magic beans), RTTT set out to very deliberately label a bunch of students, teachers, schools, districts and states as losers. So, yay.

5. Benchmark and track progress.

The school leader (because our model here is schools run by visionary powerful CEOs) needs to have all that data so he can keep everyone on track. This data will also be useful for the civilians, and it should include comparable data that we can weigh against other schools, states, nations, and planets. One size fits all education is super because it's the easiest kind to create spreadsheets for.

6. Evaluate and share the performance of new innovations.

Except when we're competing as a way of improving? This is always the part I find mysterious about these free market fans-- the competition game is great unless I am winning, in which case people should compete for my favor, but I should not have to compete with anyone else. Bring me your great programs as tribute, and I will reward you by giving those techniques to the people you must compete against. Is there any corporate or political structure anywhere in all of human history that actually works that way?

7. Combine greater accountability and autonomy.

Another piece of thick-sliced baloney. We are great at giving charters autonomy, but we have been very insistent that they not be accountable to anyone. Their finances are to be kept secret, their education programs proprietary secrets, and their leadership should never actually have to answer directly to taxpayer and voters.

No, accountability here means that the service provider should be accountable to the corporate bosses who sweep up the proceeds from the business. Accountable to parents and students and taxpayers? That's crazy talk. They are going to cite a study by the Boston Foundation, a group set up expressly to help pry schools away from elected school boards so that visionary CEOs can have the freedom to do what they will and never have to answer to any of the little people.

8. Invest and empower agents of change.

Get your people in positions where they can make sure that the rules and the enforcement of the rules go your way. Spend whatever it takes to do that.

9. Reward successes (and productive failures).

The unstated but very important rest of this sentence is "and nobody else. And make sure that you are the one who defines success." Again, there's no proof that merit pay works, but it works great for the people who are doing the paying, because it's cheap. So let's keep doing it.

So who are these guys?

Barber and Klein would be enough of a team all by themselves. But they're not on their own here.

The parent group is the World Economic Forum, often referred to by its annual meeting location at Davos, Switzerland. The organization was found in 1971 and launched by inviting almost 450 corporate heads to come together and figure out how they would manage the world.

To better manage the world, the WEF has what it calls Global Agenda Councils.

The Global Agenda Councils are a network of invitation-only groups that study the most pressing issues facing the world. Each council is made up of 15-20 experts, who come together to provide interdisciplinary thinking, stimulate dialogue, shape agendas and drive initiatives. Council Members meet annually at the Summit on the Global Agenda, the world’s largest brainstorming event, which is hosted in partnership with the government of the United Arab Emirates.

So who are the invitation-only experts of the Global Agenda Council on Education? Well Barber is the chair, and Klein the vice-chair.

Omar K. Alghanim, Chief Executive Officer, Alghanim Industries A multi-billion dollar international conglomerate based in Kuwait, with their fingers in literally hundreds of pies from Delco to Avis.

Claudia Costin, Senior Director, Global Education, The World Bank

Jamil F. Dandany, Director, Education and Academic Programmes, Saudi Aramco A Saudi oil company, "where energy is opportunity."

Jose Ferreira, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Knewton Inc. The arm of Pearson devoted to big time data mining.

Jiang Guohua, Associate Dean, Peking University Graduate School

Shiv V. Khemka, Vice-Chairman, SUN Group Investment and private equity management group, specializing in emerging markets like India and Russia

Brij Kothari, Director, PlanetRead

Paul Kruchoski, Policy Adviser, US Department of State Yes, the US has a rep on this council, but not from Education-- from State

Rolf Landua, Head, Education Group, European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)

Mona Mourshed, Director, McKinsey & Company Consulting and investment experts, with a long history of pushing for privatization

Anne McElvoy Editor, Public Policy and Education, The Economist

John P. Puckett, Senior Partner and Managing Director, The Boston Consulting Group Like McKinsey, experts in explaining how to dismantle public education for fun and profit

Shiza Shahid, Co-Founder and Global Ambassador, Malala Fund

Andreas Schleicher, Head, Indicators and Analysis Division, OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)

Gracia S. Ugut, Executive Director, Lippo Education Initiatives, Lippo Education Initiatives One of Indonesia's biggest conglomerates. Fun story. The founder-CEO James Riedy was for a time barred from traveling to the US because of illegal contributions to Bill Clinton's campaign.

Dino Varkey, Group Executive Director and Board Member, GEMS Education Worldwide private school chain based in Dubai.

Rebecca Winthrop, Senior Fellow and Director, The Brookings Institution

Well, that just looks like a swell bunch of folks to unilaterally determine what education should look like on a global scale. What a fine, respectable group of wolves to oversee the proper management of sheep.

WEF is a systems bunch of folks, who look to make systems that work for them:

The global, regional and industry challenges facing the world are the result of many “systems” .... To enable our constituents to make sustained positive change, we work with them to understand and influence the entirety of the system that affects the challenges and opportunities they are trying to

address.

Yikes. When the world's governments and systems just don't work the way you want them to, there's really nothing else to do but override them with your own corporate super-government. The education GAME is just one small event in the Oligarchy Olympics.

Tuesday, August 9, 2016

Effect and Effect

One of the linchpinny foundational keystones of education reform is a confusion between correlation and causation.

Sometimes correlations are random and freakishly mysterious. For examples, check out the collected and recollected Spurious Correlations, by which we learn, among other things, that the divorce rate in Maine correlates with the amount of margarine consumed.

But often the correlation-related confusion has to do with mistaking effect and effect for cause and effect.

Take the classic correlation month-by-month between death by drowning and amount of ice cream consumed. At first it seems sort of random, like the divorce and margarine correlation. But with a little inspection, we see that both the rate of deaths by drowning and ice cream consumption are effects of a separate cause-- the weather. In the snow and cold of winter, fewer people eat ice cream, and fewer people go swimming.

Someone might look at pro basketball players and conclude, "Hey, they almost all have huge shoe sizes. That must have something to do with making them successful NBA players!"

When we confuse effect and effect for cause and effect, we start trying to implement ideas. Some politician says, "Well, clearly ice cream causes drowning, so let's heavily regulate ice cream sales so that we can reduce the number of deaths by drowning."

Or a parent says, "Clearly, if I start my child wearing really big shoes from an early age, he will grow up to be an NBA player."

That's exactly where we are with education reform. Test scores are the big shoes of education.

We know that students coming from families with high socio-economic status generally do well on standardized tests.

We know that students coming from families with high socio-economic status generally do well in college and the whole career thing.

These are two effects. But the promise of ed reform is that if we can get every student to do well on a standardized test (PARCC, SBA, SAT, whatever Big Standardized Test your state has landed on), then the whole college and career thing will fall into place for them.

But putting my short, tiny twelve-year-old in size twelve shoes will not make him grow as big as an NBA player. In fact, forcing him into the shoes will probably create all sorts of other problems, including making it actually harder for my child to develop actual basketball-playing skills. Sure, there will be some outliers that can be used as 'success stories," particularly if the shoe companies discover they can make a mint pushing this plan. But mostly, it just doesn't work.

The promise of ed reform, stripped of all the fancy blather, is pretty simple-- if we can get these poor kids to score well on a narrow standardized math and reading test, they should find themselves with the same opportunities for a rich and rewarding life that they would have had if they'd been born wealthy.

That's a sad con, a big case of snake oil. Worse, it has caused a diversion of resources away from actually educating students. It lets folks pretend they're working on the problems of equity and education when in fact all they're doing is throwing around a pair of extra-large shoes.But wearing big shoes doesn't turn you into a basketball player, and passing a BS Test doesn't turn you into a highly-educated child of privilege.

Sometimes correlations are random and freakishly mysterious. For examples, check out the collected and recollected Spurious Correlations, by which we learn, among other things, that the divorce rate in Maine correlates with the amount of margarine consumed.

But often the correlation-related confusion has to do with mistaking effect and effect for cause and effect.

Take the classic correlation month-by-month between death by drowning and amount of ice cream consumed. At first it seems sort of random, like the divorce and margarine correlation. But with a little inspection, we see that both the rate of deaths by drowning and ice cream consumption are effects of a separate cause-- the weather. In the snow and cold of winter, fewer people eat ice cream, and fewer people go swimming.

Someone might look at pro basketball players and conclude, "Hey, they almost all have huge shoe sizes. That must have something to do with making them successful NBA players!"

When we confuse effect and effect for cause and effect, we start trying to implement ideas. Some politician says, "Well, clearly ice cream causes drowning, so let's heavily regulate ice cream sales so that we can reduce the number of deaths by drowning."

Or a parent says, "Clearly, if I start my child wearing really big shoes from an early age, he will grow up to be an NBA player."

That's exactly where we are with education reform. Test scores are the big shoes of education.

We know that students coming from families with high socio-economic status generally do well on standardized tests.

We know that students coming from families with high socio-economic status generally do well in college and the whole career thing.

These are two effects. But the promise of ed reform is that if we can get every student to do well on a standardized test (PARCC, SBA, SAT, whatever Big Standardized Test your state has landed on), then the whole college and career thing will fall into place for them.

But putting my short, tiny twelve-year-old in size twelve shoes will not make him grow as big as an NBA player. In fact, forcing him into the shoes will probably create all sorts of other problems, including making it actually harder for my child to develop actual basketball-playing skills. Sure, there will be some outliers that can be used as 'success stories," particularly if the shoe companies discover they can make a mint pushing this plan. But mostly, it just doesn't work.

The promise of ed reform, stripped of all the fancy blather, is pretty simple-- if we can get these poor kids to score well on a narrow standardized math and reading test, they should find themselves with the same opportunities for a rich and rewarding life that they would have had if they'd been born wealthy.

That's a sad con, a big case of snake oil. Worse, it has caused a diversion of resources away from actually educating students. It lets folks pretend they're working on the problems of equity and education when in fact all they're doing is throwing around a pair of extra-large shoes.But wearing big shoes doesn't turn you into a basketball player, and passing a BS Test doesn't turn you into a highly-educated child of privilege.

Monday, August 8, 2016

Summative School Ratings: Not So Great

Chad Aldeman took to the Bellwether blog to make his case for summative school ratings (grades) under the loaded headline "Summative Ratings Are All Around Us. Why Are We Afraid of Them in K-12 Education?"

Of course, plenty of us, maybe even most of us, are not "afraid" of slapping a grade on schools. There just don't appear to be many benefits, and plenty of harm done. Aldeman provides a list of his positives. Let's see how they stack up.

1. Summative ratings are all around us.

Perhaps Aldeman somehow skipped that part of childhood where some adult authority figure said, "If everyone else jumped off a cliff, would you do it, too?" He correctly notes that ratings are all the rage, from Amazon to Rotten Tomatoes. But he also notes that customers who are interested in purchases will read the reviews, and reading through all the reviews on Amazon or Yelp is pretty much the opposite of a summative rating.

Of course, this sort of system doesn't always work out well. TripAdvisor, an app and service that collects reviews (and makes summative ratings) of hotels and motels, ironically itself gets a one star rating from Consumer Affairs, backed up by hundreds of tales of the rating service being skewed in any number of ways, often because of one sort of relationship or another with those being rated.

Aldeman might also have noted the long-standing summative rating used in the investment world, where investments are rated A or AAA or some lesser letter. If you think back to 2008 and all the people who lost their shirts, pensions, or homes because a whole lot of highly summatively rated investments turned out to be the result of big fat lies-- well, that summative rating system failed as well.

So there are lots of summative rating systems out there-- and many of them kind of suck. And yes, some folks on my side of the debate table sometimes trot these summative ratings out-- I don't like it any better then.

2. Summative ratings are popular

No doubt about it. When it comes to some low-stakes decisions, people just like a simple up-or-down rating system. But the higher the stakes, the less satisfactory a simple summative rating system (I'm just going to start calling this SRS because I'm a lazy typist). Lots of people would say, "Let's just go to a five star restaurant, whatever it is." Hardly anybody says, "I would sign up for a romantic match site that just rated all the people with stars, and I would marry any five-star person, sight unseen."

Summative ratings are popular because people don't like to agonize over low-stakes decisions. But when it comes to high stakes decisions, they want as much information as they can get, not a quick summary. Schools, for most parents, are not low-stakes decisions.

3. Summative ratings are simple and easy to understand, but they’re not one-dimensional.

Here Aldeman and I disagree. Of course summative ratings are one-dimensional. That's the whole point-- to take a whole bunch of dimensions and simplify them to one quick, easy rating. Now, here's where we agree:

Inevitably, there’s no one “best” car for everyone, and there will never be one “best” school for all kids, but that doesn’t mean we should throw up our hands and give up in trying to help families weigh their options.

True enough. I just don't believe that a SRS is a useful tool in this circumstance. If you are reading through the Amazon reviews or the Consumer Reports descriptions or the college guide narrative paragraphs of description, that is not a summative rating.

4. If states don’t rate their schools, someone else will.

Oh, Chad Aldeman. I've read lots of your stuff, and you are definitely better than this argument, which can also be used to establish the State Department of Graffiti, the State Meth Production Lab, and the State Office for the Production of Bad Fan Fiction. These are all things that someone else will do anyway.

For that matter, shouldn't a right-tilted thinker like Aldeman prefer that someone else do it? After all, do we look to McDonald's for a rating of their own menu, or depend on car reviews from car manufacturers? I'm not an advocate of SRS for schools at all, but I would think that the same folks who think most education functions should be run by private enterprise would not also suggest that private enterprise run the rating system. After all-- whether we're talking public schools or charter schools, the state is certainly not a disinterested party.

No, this idea fails twice.

5. ESSA’s authors clearly envisioned states creating summative ratings.

Absolutely agree. ESSA clearly calls for a SRS. Of course, ESSA clearly respects the right of parents to opt out of the Big Standardized Test while also clearly demanding that states force at least 95% of all students to take that test. And that's before we get to the spirited arguments between Congress and the USED about what ESSA says. So I think it's safe to say that ESSA is still working out some of its issues.

6. Summative ratings force schools to improve.

If there’s one thing that’s clear from 13 years of No Child Left Behind, it’s that schools respond to external accountability pressures. They sometimes respond in unhelpful ways, of course, so the challenge is to design accountability systems that encourage schools to focus on measures that truly matter (which is all the more reason states should be involved).

Let me edit that down a bit: If there's one thing that's clear from 13 years of No Child Left Behind, it's that schools pretty much always respond to bad external accountability pressures in terrible ways.

NCLB, RTTT, and RTTT Lite (Waiver edition) all made test-and-punish the centerpiece of accountability, and that predictably narrowed the focus of every school in the country to "whatever is on the test." Schools did not improve. Some schools got their test scores to go up, but there isn't an iota of evidence that test score increase has anything in the world to do with a school getting "better." All of this guaranteed that SRS would be a joke, a letter grade based on how students did on a bad, narrow test.

Furthermore, this point falls back on the old notion that if we want schools to improve, we will have to force them to do it with threats and coercion. Reformsters really need to catch on that approaching schools and teachers with an attitude of, "You guys suck, so we are going to beat you into shape," really isn't helping.

A Few Points of My Own

There's a whole discussion to be had about whether SRS actually tell us anything or are just one more way to say "This school is rich, and this school is poor." In other words, data already readily available. And as always, I'd feel better about "finding" these troubled school is the response was more, "Let's get this school the support and resources it needs" and less "Let's turn this school over to a charter operator or a turnaround expert."

But let me skip those issues and just list three objections to the idea of summative school ratings.

1. Campbell's Law Again

The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.

If this law hadn't already existed, ed reform would have sparked someone to invent it. If high stakes are attached to these kind of school measures, they transform schools from an institution whose primary purpose is to educate students into an institution whose primary purpose is to keep the numbers of its measure up.

2. Reductive Measurement Further Warps That Which It Measures

If we decided that the summative measure of buildings was going to be based only height and width, we would end up with really cool buildings not deep enough to actually step into. If we decided the summative measure of food would be based strictly on how many colors were displayed, we would end up with garish food that tasted terrible.

When your SRS is based on an over-simplified measurement that ignores several dimensions of whatever's being rated, you end up with useless ratings and screwed-up things being measured. And when you are trying to come up with a simple summative rating for something as complicated as a school, it's absolutely guaranteed that your rating will ignore a huge number of critical dimensions. We've already seen this in thirteen years of schools being rated on math and English scores, and so cutting everything from recess to science to arts.

A school is a hugely complicated system of live human beings, each one of which is also highly complex. There is no way to some up with a summative rating that is not reductive well past the point of usefulness and not well into the realm of destructiveness.

3. School Turned Upside Down

One of the side-effects of the past decade-plus of accountability has been to turn schools upside down. Because the school must keep its numbers up and meet its accountability requirements, the school is no longer there to serve the student-- the students are there to serve the school. Is Chris dragging us down with lousy test scores? We'd better pull Chris out of a bunch of classes and park Chris in the land of remedial test prep every day until that score comes up.

Charters have always recognized this-- let a bad student in to ruin your numbers and there's hell to pay. Better to counsel them out or keep suspending them till they give up. And public schools are not immune. In Upper Darby, PA, where the district is discussing moving the school attendance boundaries, parents are objecting because Those Students will hurt our school rating.

When the primary objective of a school is to make its numbers so that its summative rating doesn't take a hit, it's very easy to start seeing students as obstacles or problems-- not the whole purpose of the school.

Ultimately my objection to summative ratings for schools is that instead of giving schools one more tool for helping students, they get in the way of doing that job-- the most important job we have in schools.

Of course, plenty of us, maybe even most of us, are not "afraid" of slapping a grade on schools. There just don't appear to be many benefits, and plenty of harm done. Aldeman provides a list of his positives. Let's see how they stack up.

1. Summative ratings are all around us.

Perhaps Aldeman somehow skipped that part of childhood where some adult authority figure said, "If everyone else jumped off a cliff, would you do it, too?" He correctly notes that ratings are all the rage, from Amazon to Rotten Tomatoes. But he also notes that customers who are interested in purchases will read the reviews, and reading through all the reviews on Amazon or Yelp is pretty much the opposite of a summative rating.

Of course, this sort of system doesn't always work out well. TripAdvisor, an app and service that collects reviews (and makes summative ratings) of hotels and motels, ironically itself gets a one star rating from Consumer Affairs, backed up by hundreds of tales of the rating service being skewed in any number of ways, often because of one sort of relationship or another with those being rated.