Back a month or so ago we had a call from

the Building Bridges Initiative and their "report" on education reform, signed by education reformsters running the gamut from A to B.

Now, as a sort of sequel, we had an

hour-long confab with Rick Hess and Arne Duncan about the future of bipartisan ed reform. Or rather the lack thereof. Especially the lack thereof. I watched it so you don't have to, and while Arnie does not exceed expectations, this is my favorite intellectually honest version of Hess.

Moderator Erica Green (New York Times) says we're looking at the landscape since 1983, and we are currently standing at a "new inflection point." She also says we've seen reform efforts throughout the years that tried to answer that "call to action." But no bigger call to action than three years ago "when the nation was literally at risk," which is a fun way of acknowledging that A Nation At Risk was overblown hype. Green says she will argue "to the ends of the earth" that children bore the brunt of the pandemic. Now, she says, "we're back on autopilot."

So she opens with "What happened to the sense of urgency?"

Hess calls out Congress as a clown car. "So much of what passes for leadership has become performative." What gets rewarded is the people who do things to get attention and not those "who slog away." The easiest thing in the world, he says, is to have big flashy ideas and new exciting innovations, and the hard thing is to show up every day and make good decisions. "We spend a lot of time rewarding people who talk in ways that sound exciting and that has distracted us mightily." I wish he defined us more precisely, because he's saying things that teachers, who have tried really hard to avoid all the reformy distractions, can relate to mightily.

He pivots to absenteeism and bullying and unsafe schools and we have lots of labels and initiatives but not much stomach for seeing things through.

Duncan thinks we're adrift. He wants to have clear goals in education. "We always debate small ball stuff." Oh, Arne.

But I'm going to interrupt here because both have touched on what I think is critical, and why their idea of education reform is flagging--

Education issues are specific and local; ed reform wants to be broad and national.

Showing up and doing the work is specific and local. Issues like absenteeism and bullying and etc etc etc are specific and local. National Ed Reform has insisted that solutions can be scaled, that we can have an idea that will fix education in 50 states. It has repeatedly run aground on that premise (Common Core is only the most spectacular example).

Okay. Back to the talking.

Arne doesn't see anyone talking about big bipartisan nation-building goals or strategies to attain them or data about who's making progress. Because, as we've repeatedly seen, Arne learned nothing from his time at USED.

Duncan wants to know, for instance, which ten districts are doing the best at recovery from covid. He will never know, because there's no way to quantify that. And it doesn't matter, because the approaches are largely specific and local.

Hess suggests a less rose-colored view of the Clinton-Bush-Obama years. Groupthink allowed people to hide a lot of bad ideas. You go, Rick. So he's for productive conversation and finding places to agree and "where we disagree, let's disagree like grownups."

Hess: Campbell's Law has just eaten our lunch over the last twenty years. He uses that to complain about grade inflation and fake grad rates and I wish he'd dig a little deeper, but he points out that Duncan's desire for data is doomed because it's hard to trust the kinds of instruments that are being used to gather data. Yup. Can we cancel the Big Standardized Test now, please?

Green winds her way past nostalgia for when groups were fighting through robust debate and now we've got fracturing and teachers in trouble for what books they teach and maybe we need to redefine what ed reform is? Are graduation rates and test scores and NAEP scores just "a relic of a different time?" And I'd say, well, "relic" suggests there was some golden time in the past when they were useful. Maybe instead ask "Are we finally willing to admit that some of that reformy baloney failed?"

Hess says maybe that time of reform was an atypical time. Hess argues that 1983-2013 was a big time for accountability and teacher evaluation and most of our history has been arguing over books and history to teach. I don't know--in the late 70s my professors were talking about the accountability pendulum. But the culture debate has been eternal. Hess adds that families may not be thinking about school reform the same way. "If they ever were," I'd like to add, crossing my fingers that Duncan doesn't bring up disappointed suburban moms again.

Duncan wants everyone to agree on goals and actually points out that different locations would have different ways to achieve those goals, highlighting once again the huge disconnect between the words that come out of his mouth and the policies he championed.

Duncan says that parents got left behind during COVID, which is some Grade A bullshit on several levels. Parents have said they

were largely happy with how their local district handled things. Then he's back to his old chestnut that parents don't really know how well their students are doing. "They think everything's okay, but it's not." He wants to measure stuff.

Hess asks Duncan what his goals are, and it's the same old thing--preK, third grade reading, grad rates, college rates.

Green is back. She wants to know who "we" are, too. Who is supposed to lead all this?

Duncan says top down and bottom up. Mayors. Governors. Senators. Parents should beat down doors. When he was in DC he was critiqued for going too fast, but he believes he went too slow. He doesn't have an answer. Everyone. He feels that nobody is really agitating for the things he wants (Hmm... what might that mean). He wants voters to hold politicians accountable for school stuff, but it doesn't happen. He has no thoughts on why not. Weirdly enough, school boards do not appear anywhere in this answer.

Green asks Hess--who is the great convener here? And is it possible?

Hess tells the story of how NAEP was created to give governors incentive to step up.

Green calls back to a "really excellent" Mike Petrilli op-ed in NYT, which must b

e his No Child Left Behind nostalgia piece. She asks if we're just not saying the quiet parts out loud "like we did in A Nation at Risk or NCLB" and ho boy-- I don't know about the quiet parts, but A Nation At Risk certainly said some made up parts out loud.

Hess says ANAR was pretty crude. NCLB "was so insistent that we knew what worked and if we collected test scores and held schools to the fire then kids would do better." That was misleading about what we knew about what worked and how well we could trust the measures, and it cut parents out of the equation by saying it was "schools and schools alone and there are no excuses" He offers an illustration-- if the pediatrician says my kid is a little heavy and we should lay off the snacks and I take the kid home and open a bag of doritos, we don't say the pediatrician is bad. Which sounds very much like the kind of story that hundreds of teachers used back when reformsters told us we were whiny excuse-making babies back during NCLB.

Hess gives credit to NCLB for changing a culture of parent blaming, but now superintendents and principals are afraid to tell parents to take away cell phones and supervise homework and get to school. And we never did talk about that honestly in any of the big reforms.

Duncan moves on to absenteeism as an example of nitty gritty roll up your sleeves that he thinks people don't have the appetite for.

Green is still upset that we told kids their whole lives that school was the most important thing, but we opened bars first (not for the first or last time, I think that people who do/report policy work in DC or NYC desperately need to take a long out of town sabbatical). Also, she's concerned that during the shutdown many young folks got jobs and started their lives. I get the concern over the message that schools (and students) aren't really the most important thing, but that not-so-important message has been constant from long before the pandemic, communicated clearly through funding and all those politicians who don't run on education because there are no large numbers of education voters. Honestly, folks--talk to more teachers, whose morale is battered daily by this basic fact of life in this country.

But she's worried that maybe we should just say that the system that is supposed to be so important is "fractured." But she's pushing back on Arne's idea of telling principals to go find their kids.

Arne says some stuff, but I'm going to pick out the assertion, again, that if kids get a better education, they will make better money, because this ignores other economic realities. Minimum wage jobs will still pay minimum wages, even if they hire someone with a college degree, and what we learned in the pandemic is that there are lots of working-poverty wage jobs that we absolutely want to have filled, and if every student in the country got a college degree, those jobs would still exist and still pay poorly. Put another way, advanced education gives you a better shot at coming out ahead in the competition to avoid poverty wages, but competition will still exist and some people will still lose.

More talking. Agreement that pandemic responses were bad.

Hess says education needs to be reconfigured and fixed. Also, Hess thinks the book ban discussion is dishonest on the ALA and PenAmerica side. Parents have the right to be heard, but not to dictate. We are dismissive of parent concerns, but are reluctant to tell them to monitor smart phones.

Green pushes back a bit--everyone is climbing on educators to Get These Kids Caught Up but also legislators saying "If you use this book we will fire you." What do we do with that?

Hess shoots for nuance in a short space--12th graders should be able to read Bluest Eye, sixth grade libraries shouldn't have graphic sex in them, there has to be honest discussion and professionals have to acknowledge some legitimate parental concerns. But the whole debate has become performative.

Duncan characterizes the book debate as a rabbit hole and total waste of time and energy. "Their phone is going to corrupt them long before any freaking book." He looks a little sleepy. But he thinks they're spending more time scaring parents than actually pursuing educational goals is a waste. No argument here. "It's a devastating lack of leadership." Well, I doubt it. Not sure what kind of leadership would have stopped M4L and the MAGA crowd.

Green asks again who leads a breakthrough. Duncan reiterates the point about having conversation and honest debate, but that's not really an answer. Give parents real info. He has a real insight here--what's happening on the NAEP? "That's what's happening on the state level. That's not my kid. Who the hell cares?" Real parent empowerment by giving them real information. I cannot begin to describe how much heavy lifting "real information" is doing here, particularly since it is also laden with the premise that parents are currently given fake information.

Hess stumbles for a bit--honestly, it seems like this conversation is sucking all the energy out of the room--but arrives at the idea that one lesson of NCLB is that parents compare what they know about their kid and their school to what a single standardized math and reading test says, and they pick what they know first hand. "I trust my eyes, not your fancy data points." I'll note that in twenty years, reformsters have never come up with a good response to that, nor have they paused to consider that this widespread response might tell them something about their fancy data points, like the data collected isn't all that great, or that it represents such a tiny sliver about what parents care about in their schools that it's useless. Duncan is the poster boy for "If people really understood the situation, they would agree with me," an approach that almost never works and which, in the reformster movement, leads to the difficult to manage position of "Parents should be entrusted and empowered even though they have no real understanding of what's going on."

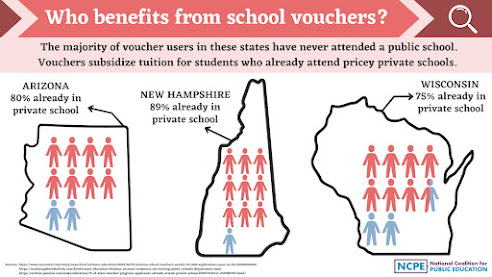

Hess contextualizes choice here. Pre-pandemic, it was mostly about rescuing students in bad urban schools. The post-pandemic explosion he sees as driven by a desire to give all families more choices. I'm not fully convinced; the post-pandemic explosion of vouchers and neo-vouchers hasn't been a grass roots movement, and these bills still aren't being passed democratically by voters. They are almost exclusively coming because right wing folks have captured legislatures and are feeling emboldened. Certainly there's been some noise on the ground to help this process along, but that's only a small piece of it. And of course it depends on the state or district.

Hess also argues that choice (citing DC) leads to parents paying closer attention. That's an interesting notion.

That gets us to the Q&A and I'm not going to sweat that (Duncan says yay mastery learning, and talks like a Republican about how much money has been sent to schools and where's the accountability), because we can note a couple of things here.

One is that neither one of these guys, at least one of whom is pretty smart, don't have any thoughts about how the old reformster coalition might reform. It won't, and I can think of at least two reasons.

One is that reform in the Clinton-Bush-Obama mode was largely a national undertaking, a series of attempts to set national policies that would have national effects. But the pandemic underlined, twice, that most education issues are specific and local. Building closures, teacher expectations and duties, attempts to cope--the discussion brough these issues up without noting how widely they varied district to district. Education issues are specific and local. Education issues are specific and local.

The choice crowd already knows this. That's why they're hammering states (and calling for the federal ed department to be shuttered) and calling for their people to get in there and commandeer school boards. The most extreme of this crowd is not even really interested in choice, but in recapturing with both diverting tax dollars to private (Christian) school and pushing the religious agenda into public schools. And this dovetails nicely with those who still want the Friedman dream of dismantling public education and making schooling a commodity that each family is responsible for procuring on their own.

Those folks have left the old reformster crowd in the dust. The bipartisan movement that they're nostalgic for is done. Of course Duncan and Hess can't come up with any names for leadership forward; as Hess correctly notes, the big names are all busy making noise for clicks and attention and money from big contributors. They're also, it should be noted, angling for cushy platform gigs with advocacy groups and think tanks. I imagine that when MAGA education dudebros like Rufo and Walters and DeAngelis look back at the Clinton-Bush-Obama era they might think, "Well, it was nice that they kind of broke some ground for us, but they are dinosaurs, tinkering around with scalpels. It's up to us to get out the flamethrowers and do what must be done. They're history. We're the future, and we don't need to form coalitions--we need to bend people to our will."

The modern reformster movement, as much space as I spend writing about it, is dead. Much of what it wanted--high stakes testing, charter schools, nationalized standards--is now part of the education status quo. As this conversation shows, one of the reasons they can't muster a new coalition is that there really aren't any goals to rally around. Duncan's four goals are not matters for national policy, and they're not particularly clear or specific anyway. And as they sadly note, the angry Moms and the performative flamethrower guys have all the attention anyway.