Wednesday, October 11, 2023

How Vouchers Bust State Budgets

Monday, October 9, 2023

Hess, Duncan, and the End Of National Ed Reform

Re: Microschools and the hype cycle

But other families latched on to the growing array of microschools that, at least for the educators who created them or the families who used them, solve any number of the problems plaguing public education: youth mental health is in crisis, teacher morale is flagging, voluntary community associations are desiccated, students are often disengaged if they’re showing up at all, bonds of trust between schools and families are fraying.

It takes a special kind of cynic to imagine the current blossoming of small learning environments where teachers are free to realize their peculiar vision for what learning could look like and partner with families to make it happen is the brainchild of a few voucher advocates.

Sunday, October 8, 2023

Ed Tech Can Be Useful

ICYMI: Applefest Edition (10/7)

Friday, October 6, 2023

My Testimony For The PA House Education Tour

Good

afternoon, and thank you for allowing me to speak before you today.

My name is

Peter Greene. I retired after 39 years as an English teacher, with 38 of those

years spent in Franklin Area Schools up in Venango County. It’s the same district that I

graduated from. My two older children went through that system, I have a pair of

twins passing through now, and my wife teaches in a neighboring district, so I

have many stakes in Pennsylvania education. For the past decade I’ve been

writing about education; my works has been in the Huffington Post, the Washington

Post, and Education Week. These days I write regularly about education for

Forbes.com and The Progressive, as well as my own blog.

I’ve spent a

lot of time tracking and studying education policy trends across the country. Pennsylvania

does a pretty good job, and Pennsylvania teachers do a good job as well.

How do we do

better? Today I’d like to focus on meaningful accountability.

There are

few policy decisions that have had a more toxic effect on education than the advent

of high stakes testing. Reducing the impact of Keystone and PSSA testing on

teacher evaluations was a step forward. It would be even better to reduce the

weight of those tests to zero, including taking them out of the assessment of

school effectiveness.

The PSSA and

Keystone exams do not provide useful data to classroom teachers. The information

that they supply comes too late and too vague to be helpful, especially because

teachers are forbidden to see the actual questions that students had trouble

with. Nor do the results provide information teachers didn’t already have. No teachers are looking at Keystone

results and saying, “I had no idea that this student was having trouble with

the material.”

Twenty-some

years of high stakes testing has twisted education out of shape. Administrators

and teachers should be making curriculum and instructional choices based on the

question “will it help us provide all students with a full, effective, well-rounded

education,” Instead, too many schools have been asking “Will it raise test

scores?”

In my own

subject area, testing has been particularly corrosive. Teachers spend much of

the year on test prep, which means practicing taking that particular kind of

test. The test does not involve reading whole works and then reflecting and

digging deeply into the ideas, but reading a short excerpt without context and

answering a handful of multiple choice questions quickly—right now—That’s the

test, so that’s what students practice. Short excerpts of context-free readings

have replaced study of full works, and that’s a big loss to students.

We can hold

local administrators partly responsible for these kinds of choices or for the

over-scheduling of practice tests, but state policy has pushed them by putting

too much value on these tests.

Do we need

accountability for schools? Absolutely. But these high stakes tests don’t

provide it.

An effective

assessment is a tool built for a particular purpose, and that’s the purpose it

serves. A really good Philips head screwdriver works great for putting in Phillips

head screws. It does not work for slotted screws, and it doesn’t work as a tape

measure or a router or a saber saw. To create a solid accountability system, it’s

necessary to answer the questions accountable to whom, and accountable for

what? The Keystone and PSSA systems have tried to be accountable to everyone

for everything, and to do it in a manner that looks at just a tiny slice of the

education picture.

The best

metaphor I’ve read for the high stakes system is someone is searching for the

car keys at night in a darkened parking lot. They’re looking around under the

streetlight, even though they dropped their cars fifty feet away in the dark. Asked

for an explanation, they say, “Yes, I know the keys are probably over there,

but the light is so much better over here.”

Truly

measuring educational effectiveness is hard, though there are scholars out

there working on how to do it. Pennsylvania’s tests can generate numbers that look

like hard data. Does that data reflect the full rich reality of a school? Do

they measure the effectiveness of the school or the achievement of students or

teachers? No.

Confronted

with the idea of cutting the high stakes from these tests, supporters will argue,

“Well, without the tests, how will we have accountability? How will we get a

picture of how well schools are doing.” My reply is, “You aren’t getting that

picture now, and you’re doing damage to school in the process.”

Teachers

just don’t want to be held accountable is another argument we hear, which is

simply not true. Teachers like accountability, but real accountability, and right

now the state is still looking for its keys under the streetlight.

High stakes

testing has also produced a basic dishonesty in discussion about

accountability. Too many people keep using the phrase “student achievement”

when what they actually mean is “student score on a single standardized math

and reading test.”

One other

important point—while we know that test scores correlate with student

socio-economic background, no research has ever shown that increasing a

students’ test score improves their life outcomes.

There has been so much discussion about making up

for educational opportunities lost during the pandemic. Removing high stakes

testing, or at least the high stakes, would instantly give schools and teachers

additional weeks of time in the school year, and it wouldn’t cost a cent.

High stakes

testing has also been damaging by feeding the notion that schools are failing, buttressing

the case for some alternatives to public schools. I urge you to resist those

arguments. In particular, I’m asking you to resist the continued push for more

school vouchers in Pennsylvania.

The most

recent version of the Lifeline Scholarships vetoed by the governor, and the

Pennsylvania Award for Student Success program passed by the Senate are

certainly more restrained voucher programs than we’ve seen in previous years or

in some other states.

We don’t have

a lot of voucher experience in Pennsylvania beyond the Educational

Improvement Tax Credits (EITC) and Opportunity

Scholarship Tax Credits (OSTC), and we don’t know much about how those are

working because so little accountability is attached to them.

But we do

know a lot about how vouchers work in other states, and we need to pay

attention to those examples.

For one

thing, we know that voucher programs tend to expand, even when they start as

small as the most recent voucher proposals in Harrisburg.

Programs

typically start on a small scale with the argument that they are just to rescue

a few students living in poverty and attending so called failing schools. States

start with a traditional voucher that pays tuition at a private school and then

expand to ESA vouchers that give families money to spend on any number of

education-adjacent expenses.

States start

with caps on eligibility, including caps on family income and requirements that

the students be moving out of public school then the program expands toward

universal vouchers. In the past two years six states have expanded their

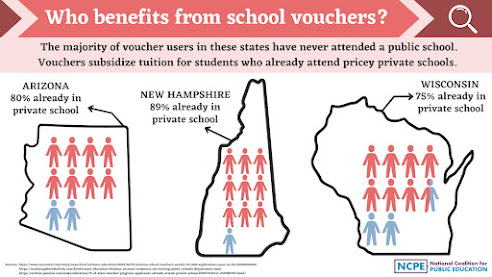

programs to universal ESA vouchers, meaning tax dollars can flow to any student.

That means that a wealthy family that never enrolled their students in public

schools can still collect taxpayer money. This kind of inevitable expansion

turns vouchers from a rescue for the poor into an entitlement for the rich.

Consequently,

voucher programs also expand in cost. In New Hampshire, a voucher program was

sold to the legislature with a projected cost to the state of $130,000 per year.

Two years later it was almost $15 million and rising. That rising cost can hit

families as well. In Iowa, when the voucher system was expanded, many private

schools immediately raised tuition costs.

We know that

without sufficient state oversight in place, vouchers often give rise to pop up

schools. Rent a store front in a strip mall, advertise your school or service,

market hard to collect a batch of enrollments with their voucher dollars,

provide substandard service, and go out of business—the average life span of

these schools is about four years. Proponents will argue that this is just the

market working, that families are providing accountability by voting with their

feet. But that comes at the cost of a year or more of a child’s education. If

we are concerned about the time lost due to pandemic closures, surely we must

be equally concerned about keeping fraudulent and incompetent actors from wasting

irreplaceable years of a young person’s education.

Fortunately,

the pop up voucher schools do not dominate the voucher market place. We know

that the vast majority of vouchers are used in private religious schools,

including schools whose stated mission is not to educate students, but to bring

them to Christ.

We know that

many of those schools teach questionable content. The war between the states

wasn’t really about slavery. All Muslims hate America. Satan created modern

psychology. Humans and dinosaurs lived together. All taught in some private schools

receiving taxpayer dollars.

We know that

those private schools often discriminate. Among the private schools accepting

vouchers across the nation, we find those who will not accept students with

special needs, or LGBTQ students, or students with an LGBTQ family member, or students

who are not Christian. We find schools that will only accept students who don’t

listen to secular music, who are born again Christians, or who have born again

Christian parents. One school in North Carolina does not require teachers to

have a license, but they do have to demonstrate their relationship with Jesus

by speaking in tongues. All in schools receiving taxpayer dollars.

Not only do

states not step in to stop such taxpayer funded miseducation or discrimination,

but most voucher bills are now written with specific clauses saying that those who accept voucher

dollars are not state actors and that the state may not in any way

interfere with how the school operates or teaches. Both the most recent version

of the Lifeline and PASS vouchers include that language.

Voucher

programs promise school choice, but in fact, the choice is the school’s, not

the family’s. Families that do not meet

the school’s requirement, or whose voucher still won’t cover the tuition cost,

get no choice, and their public school will have even fewer resources to meet

their needs. Draining public school funding for a voucher program is not the

way to fix Pennsylvania’s unconstitutional school funding system.

There are

other accountability problems with vouchers.

A voucher

system disenfranchises taxpayers who don’t have children. If you have no school

age children, you have no say in how the taxpayer dollars in that voucher are

spent. There is nobody for you to hold accountable. And because vouchers move

the purse strings from your local elected school board to officials in the

state capital, local control is lessened. In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis found

that four private schools have programs he disapproves of, so he cut off their

access to vouchers. Those parents have no recourse.

Vouchers avoid

accountability to the voters. No voucher program has ever passed a public vote

in a state. Voters reject the idea of using tax dollars to fund private

religious school tuition. These days supporters call vouchers scholarships because

the term voucher tests poorly with audiences. So voucher fans try other ways,

despite resistance.

In Texas,

where rural legislators of both parties recognize vouchers as a threat to their

public schools, Governor Abbott is holding a special session to try, again, to

force passage of vouchers. In New Hampshire, a voucher bill was proposed, over

3000 people showed up at the capital to argue against it. So the legislature

withdrew the bill, and slipped vouchers into the budget instead. That’s the

very opposite of accountability to the voters.

Vouchers dodge

accountability to parents. The voucher deal is simple—the state tells parents

here’s a few thousand dollars. Now making sure your child gets a decent

education is your responsibility, not the state’s or the community’s. For the

cost of a voucher, the state absolves itself of any accountability for that

child’s education.

It is

absolutely true that every child deserves a full, rich education, no mater what

they zip code or family’s resources. But school vouchers do not get us there.

It is true

that Pennsylvania has not always perfectly met its promise to provide a quality

education for every child, hence the recent court order for better funding. But

the solution is not to buy out families’ claim to that promise with a small

slice of taxpayer money and say, “Go navigate an unregulated marketplace on

your own. If you’re unable to get into the school you want, or your child ends

up in a substandard private school, that’s your problem.”

Of course, education

is not their problem alone. All of us depend on and benefit from a strong and

accountable public education system, and that’s where I hope legislators will

direct their efforts. Thank you.

Wednesday, October 4, 2023

Microschools for Dummies

Says the Microschools Network website, "Imagine the old one-room schoolhouse. Now bring it into the modern era." Or imagine you're homeschooling, and a couple of neighbors ask if you'd take on their children as well. Or imagine you're cyberschooling with seven kids in your kitchen. Or imagine you wanted to start a tiny pop up school.

An intentionally small student population,

An innovative curriculum,

Place-based and experiential learning,

The use of cutting-edge technology, and

An emphasis on mastering or understanding material.